According to some estimates, there are at least 4200 religious and spiritual traditions. This doesn’t even count isolated cultures around the globe, nor all those which have gone extinct. While they obviously share some traits, all these tradition seem to be radically different one from an other.

This aspect is often emphasized by both sides of the religious debate. Atheists / non -religious people frequently point out to this as evidence that they are nonsense (“How thoughtful of God to arrange matters so that, wherever you happen to be born, the local religion always turns out to be the true one” – Richard Dawkins). “Believers”, on the other hand, frequently accept through an act of faith the claims of their own religion, while dismissing all others as false.

Both these perspectives share an underlying assumption: the value of a religious or spiritual tradition lies in its “truthfulness”. And it is typically implied that these “truths” (or lack thereof) have to be evaluated in terms of how factually correct the various metaphysical, historical, or descriptive claims are. But is that the most useful way to approach a religious text, story, ritual or tradition?

Let me start with the quote I use at the beginning of my lecture series about religion, and how religion and science can go hand in hand. “All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened – Ernest Hemingway“

I do think that is really on spot, and it cuts really well into understanding religious teaching.

What is “true”?

One option is to call truth that which can be objectively demonstrated to be factual, as is done in the natural sciences. That’s useful and practical, of course. If I had to choose the one thing that has most transformed human civilization, in a positive way, I’d pick science without any doubt.

Unfortunately, very often, science-minded people have the tendency to disregard as “untrue” or “unsupported by evidence” anything that doesn’t fit this narrow definition. And typically conclude it is, thus, irrelevant. Science has the tendency to drop subjectivity out of the window. That is a positive thing when we are dealing with questions about the objective nature of the world. But, it’s rather limiting when dealing with questions about human life. Why? Well, basically anything about my life is directly and massively dependent on my subjective experience of it. Thus, while objective, a discussion about my life which disregards as irrelevant all my feelings, perception and experience is, quite evidently, pretty much useless.

Of course, once we introduce back the dimension of human subjectivity which we have tried to throw out of the window, things get both very complicated and very unpleasant. This requires us to accept the fact that what we call “reality” is mostly an illusion created by our brain. Or that, while we have been stunningly succesful in understanding the external universe, our scientific understanding about the world within our mind is still at its infancy. And, most importantly, largely ignored and poorly accepted by practictioners of the “hard sciences” and, even more, intellectuals in general.

I think the following old tale explains the issue very well:

A police officer notices Mulla Nasredin holding onto a lamp post, looking intently on the ground. So he went up to him, “What’s the matter?” Mulla replied “I lost my wedding ring, my wife will kill me if I go back home without it!”. The officer helped him look for it, but there was no sign of the ring. “Where exactly did you lost it?” the officer asked. “Oh, over there, at the other corner of the street” “Then why the devil are you looking for it here?!” asked the cop. “Well you see, old man, it is very dark over there. The light is much better here!”

So, we got a very important way to deal with “truth” through science: to be somehow able to determine that which is factually true in an objective sense is a remarkable achievement. But is is also limiting, and it misses plenty of important things. Even more crucially, it means that we can’t use the power of a scientific and rational inquiry for dealing with the things that matter most to us. There could be (and are, as far as I can tell) other “truths”. Perhaps deeper ones, as far as human life is concerned. I’d argue, thus, it may be the right time to look at the opposite corner of the street, even if seems to be very dark over there.

Back to Hemingway’s quote. How in the world can a story be truer than real events? Aren’t the real events, by definition, that which is true? And isn’t is so that all a story can do is, at best, to describe reality as accurately as possible. Well… In all honesty, is that how we ever approach any book? When is the last time you took a book and thought: “alright, let me see how factually correct this story is”? You may say that you enjoy a book, a movie, an activity (like, say, dancing) due to entertainment value, not as a source of truth. Yet, that isn’t necessarily correct. Stories and other works of art speak to us in some very deep sense, and very often you can “get” a message from them, rather then mere entertainment. We can also tell when a story is “truthful”. And funnily enough, we can tell that perfectly well even when the story is obviously “untrue” in a factual sense. For instance, every fantasy book ever takes place in what is, by definition, an imaginary world. So, could I write a fantasy story where random events just happen one after another? I could, but no one would read it because that wouldn’t make any sense. Uhm… what? How do The Lord of the Rings or Harry Potter make any sense either, since we all know perfectly well they describe 100% imaginary events? Yet, we clearly have an innate understanding of what “makes sense” – or, to put it in other words, when a story is “true” – which is entirely independent of how factually correct it is. It is the same understanding that allows us to read an Aesop’s fable and feel that it is truthful (what? don’t you know that animals don’t talk?), or to watch Pinocchio and totally get what the story is about (what? you don’t really think a puppet can become alive, do you?)

You can use a story to teach a principle, to share emotions, to inspire, even to make ideological propaganda. A story can extrapolate truth within real events, in the sense it exposes underlying mechanisms, shared perceptions, pyschological truths, and so on. Paradoxically, by manipulating the “factual” aspects of the story, the author can create something that conveys more powerfully and effectively the message. “Objective” aspects of a story can be used as literary device to express a point, and thus “talk” to the deeper structures of our mind. We can convey messages by transforming an historical event beyond recognition. Or even by creating from scratch openly non-existent worlds (as Tolkien’s Middle Earth). Or non-existent non-human beings which, nonetheless, we can recognise as fully human, or even archetypically human (as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’s monster, or Pinocchio).

Arguably, our mind is specifically designed to pay attention to this. For instance, in The (subtle) Evil Demon, I argue how science has demonstrated that human memory is NOT designed to accurately store facts, but to store “the moral of the story”. And, in fact, if we change our perspective on things (changing “the moral of the story” of our life events) our mind can alterate even drastically how we remember an event, or even create new memories from scratch. To a large extent, our moral judgement and our introspective understanding of our own (or other’s) behavior follow the same pattern. Our learning in general also mostly relies on these processes of implicit abstraction and extrapolation.

This is not a minor feature. This is not something to discard as “untrue” in the narrow sense we described. What we call reality is not a representation of the objective external world (as demonstrated by the fact that colours are not real, that the sky is actually not blue, or by the stunning saccadic masking effect). We are not biologically equipped to live in the objective world. We only can live in that illusory world created for us by our brain. Communicating with the way our brain creates this illusory world is crucial because… well, technically speaking, that is the only “reality” we will ever live in.

Is Cain and Abel’s story “true”?

The story of Cain and Abel is among my favourite parts of the Old Testament (and literature in general). And I’d argue it is as “true” as you can get, and a stunningly deep analysis on human psychology. In Beyond Good and Evil, I use that story to shred light to the forces behind the important topic of human violence. As an historical account, Cain and Abel is rather unconspicuous, questionable, and inconsistent. We get very few details about it, as it’s all contained into a couple of verses. We have no evidences that it really happened. Even if it was inspired by a true event, it’s so poor of details that basically any murder story in any newspaper is certainly preferable. On the other hand, as a psychological story, it is incredibly powerful. Arguably, and factually, Cain and Abel describes accurately the psychology of most human violence in history. And that is to a large extent precisely because it is so poor of details and so disconnected of factual baggage. It is an abstraction, which allows us to use it in all sort of context rather than in the limited setting of physical reality. This is the same thing we do with math. To notice the existence of “2 apples” in front of us is useful information. The fact that an abstract concept called “number two” exists outside a specific physical context, on the other hand, is a different way in which things can be “true”, and “useful”.

So, what is the right way to interpret it the story of Cain and Abel? As a poor historical account of a specific murder? Or as a powerful psychological account on human nature? I’ll go with Hemingway. The “story of most violence”, the psychological description of one of the key pathways that lead to the darkest expression of human behaviour, is to me more interesting than the factual description of a random murder. It is, at the very least, a different sense in which things can be “true”, regardless (and, to some extent, because) of they factual innacuracy. Just as the number two can be a useful concept regardless the fact you can’t ever withness it in nature as disconnected from material objects. The story of Cain and Abel is, as far as I can tell, very real. As Hemingway put it, truer than if it really had happened. So… did it actually happen? Was a person called Abel murdered by some person called Cain at some specific moment in history, in a way that is compatible with the way the Bible describes it? Maybe. I don’t know. I don’t care. I don’t think that’s the point.

Re-inventing religion… or simply interpreting it correctly?

As I just argued about the story of Cain and Abel, or earlier on these pages about the holy sound of thunder, it is certainly possible to see all sorts of religious teaching as a spiritual guidance to our lives, rather than factual claims. That said, obviously we could ask ourselves whether or not this way to interpret religious or spiritual messages is the right one. I certainly think it is, to my knowledge, the best way to do so, for the reasons I’m going to highlight.

This way to approach the topic is, I have found, very appealing to people. Many see it as interesting and useful, as it promotes communication and peace rather than hostility and fundamentalism. It is a door to allow people of all religions or from a scientific background to have a shared framework to discuss about religious topics. As always, of course, not everyone would agree. In particular, people who are are strongly embedded into a specific religious tradition, especially when they think of other ones as inferior or false, may experience this as a disrespectful “corruption” of their truth. Similarly, fundamentalist atheists tend to dislike this approach, seeing it as apologetic of something stupid or backward, or simply as a pathetic clutching at straws in order to keep alive something that has been “debunked”.

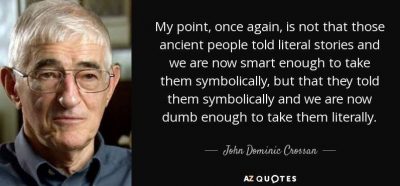

As usual, I don’t question people’s beliefs. I’m not a judge. I’m an explorer. I’m simply someone who is interested in learning about different things and having informed discussions. I’m interested in how to live a meaningful life and, if possible, helping others to do the same. If someone doesn’t find my approach useful or meaningful, that’s fine. But let me briefly address the specific objection that this approach misrepresents or distorts the actual and original meaning of religion. Not only plenty of people today see religious in other ways, but this is very likely to be the way they were originally intended. So… What evidence is there that religious stories were intented as factual accounts in the first place? As far as I can tell, none. On the other hand, although I’ll leave discussing the details to an other time, I think all the evidence indicates the exact opposite. Sure, some people (both those who support it and those against it) think the religious messages can only be interpreted in a literal way. But simply because some people believe that, it doesn’t make it correct.

I think it really matters to, at the very least, propose this framework for two reasons. First, the failure to see that religion and science describe different things is the main source of miscommunication (and hatred) between the two camps of religious and non-religious people (along as between different religions). The other reason… well, let me tell it with a joke (named the funniest religious joke of all times; author: Emo Philips)

Once I saw this guy on a bridge about to jump. I said, “Don’t do it!” He said, “Nobody loves me.” I said, “God loves you. Do you believe in God?” He said, “Yes.” I said, “Are you a Christian or a Jew?” He said, “A Christian.” I said, “Me, too! Protestant or Catholic?” He said, “Protestant.” I said, “Me, too! What franchise?” He said, “Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Baptist or Southern Baptist?” He said, “Northern Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Conservative Baptist or Northern Liberal Baptist?” He said, “Northern Conservative Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region, or Northern Conservative Baptist Eastern Region?” He said, “Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region.” I said, “Me, too!” Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region Council of 1879, or Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region Council of 1912?” He said, “Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region Council of 1912.” I said, “Die, heretic!” And I pushed him over.

See, where am I heading? The obsession over the “factual accuracy” of religious teaching is arguably the most dangerous aspect of it, as history has unfortunately demonstrated. How many people have been killed or tortured for disagreeing over minor doctrinal differences, despite sharing almost in its entirely a religious worldview? How can we ever reconcile the existence of different religions, if we assume they are about factual claims? It’s logically unavoidable that, in that case, only one religion can be true (or none), and thus everything else is wrong.

While obviously not everyone who wants to discuss metaphysics wants to burn at the stake those who disagree with them, it’s a dangerous door to open. After all, if you are convinced to have access to “ultimate truths”, it’s difficult to speak about equality or tolerance, since these concepts must be embedded in humility. And what humility can there be if you have a divine access to truth?

To conclude, it seems to me that to drop the focus over metaphysical or historical “accuracy” is not just a good compromise, but the most useful way to approach religion. This approach has many benefits, primarely:

- It’s arguably closer to what the people who first came up with those ideas meant. I don’t think the “factual claims” are the point. I think they are literaly device to express something. They are tools to achieve something. As the Buddha said through the parable of the poisoned arrow to the monk Malunkyaputta, we need to avoid the trap of wasting our limited time on metaphysical speculations which lead us nowhere closer to truth nor, more importantly, closer to the ultimate goal of our spiritual practice.

- Since “the man who chases two rabbits, catches neither” (Confucius), it’s difficult to focus on both aspects at once. Particularly since, as I said, it’s precisely the process of foregoing the attempt of presenting “facts” which makes it possible to see what is “truer than if it really happened“. If we focus on religious messages as “factual truths”, we are almost bound to lose that which makes them interesting and meaningful. As one Zen master once told me: scriptures, rituals, even the own words of the Buddha (or Jesus, or whoever you want) are like the finger that points out in the direction of the moon. They are useful, but if all you do is to stare at the finger, you’ll never see the moon for yourself.

- It promotes peace and communication. This approach offers a simple explantion of why religions are so different, while all claiming to bring some “truth”, and it allows them to coexist – or, even better, to gain one from an other – . I like to express it through the mountain metaphor: imagine you want to get to the top of a very big mountain. From the ground level, there will me multiple paths from which you can begin your journey. These paths may be very from from an other. They may be on the oppposite side of the mountain, maybe be in a different nation, the people there speaking different languages, and so on. But once you start climbing the mountain, all the different paths start to converge one toward an other. The higher you get the closer they are. Until, once at the top, you notice that they all lead to the same point. So, what matters in the end? To discuss how different the paths are at the bottom of the mountain? To fight about which one is better until we killed all the heretics? Or it to start climbing towards greater heights?

+ There are no comments

Add yours