Something that accomunates most religions ( and secular traditions a well) is that we find a lot of emphasis on prescriptions, recommendations or perspectives about marriage, and intimate relationships in general.

As we are moving towards an increased openness and acceptance, many people begin to wonder about the role of the traditional institutions of marriage, such as those which still permeate our legal system, and those which are found in multiple ancient religions which are still followed by large groups of individuals.

What is the role of these traditional views nowadays, and why religious tradition prescribed certain rules rather than others? In this article I try to tackle this latter question, and try to promote and understanding of the possible forces behind the traditional views on “marriage”.

From a simple question to a complex discussion

Different societies have “prescibed” different rules, and this may turn out to be rather confusing for a modern observer. What is marriage, in the first place? Are sexual / romantic interactions between a man and woman acceptable outside it? Are such interaction acceptable only between a man and a woman, or are other sort of combinations allowed? If they are tolerated or accepted, is marriage an option in those circumstances? And if it is, how does it differ from a “traditional” familiar unit? When is it possible, or advisable, to divorce from marriage? Is it possible to marry more than one person? If so, is there a limit on how many partner we can have? Is the limit the same for men and women, or are there specific prescriptions based on gender?

In the Western tradition I grew up with, “strict monogamy” used to be the only allowed answer, but with recent developments we came to accept multiple possible combinations. Same-sex marriage is nowadays allowed in some form in multiple countries, polygamy is legal in a minority of other (mostly non-Western) countries, and in general the expression of sexuality and romance largely take places outside the legal or religious institution of matrimony. With so many possible options and different configurations, all sort of discussions are taking place about what is acceptable or advisable.

In the Western tradition I grew up with, “strict monogamy” used to be the only allowed answer, but with recent developments we came to accept multiple possible combinations. Same-sex marriage is nowadays allowed in some form in multiple countries, polygamy is legal in a minority of other (mostly non-Western) countries, and in general the expression of sexuality and romance largely take places outside the legal or religious institution of matrimony. With so many possible options and different configurations, all sort of discussions are taking place about what is acceptable or advisable.

Particularly when it comes to traditional religious perspective on marriage, there is frequently a lot of animosity surrounding these issue. Those who belong to a given tradition may see their own view on marriage to be sacred (and sometimes, consequently, different paths as “unholy” or abominable). And as we live in a global society which combines multiple traditions, these perspectives are bound to clash. To the point that some people hope to forget them altogether (possibly with the whole religious system they come from). So, how to navigate all these complex issues?

There is actually a very specific reason I am writing this. I follow several discussion groups on a few platforms, and today this was asked in a religious discussion group on facebook: why in the Quran it is stated that a man can have up to four wives, but a wife can have only one husband?

I found that to be an interesting question, and while I was trying to write an answer I realised it turned out not only to be way beyond the allowed character limit for facebook, but to deal with the role of marriage in religion in general. Eventually I figure out it belonged on these pages.

While there will be an answer to the specific question about why some traditions, like Islam, allow polygyny (having multiple wives), but not polyandry (having multiple husbands), keep in mind that these pages are not about the theological analysis of any specific tradition nor about promoting any specific perspective on life.

I’m not a muslim either, so take my description of Islam as you like, but from what I understand of the Quran and the view on marriage in traditional religions in general, there are complex reasons for that. And it is these reasons which I found interesting to discuss, so that’s what this writing is about.

As is always the case in these pages, my goal isn’t lecturing people about what they should do or to dictate what is right and what is wrong. My interest is to look at spirituality and religion from a modern, rational perspective which is entirely compatible with current science, and to see if and to what extent I can make sense of those traditions from that framework. Thus, I will try to discuss why certain tradition developed in a certain way, and what sort of spiritual, psychological or societal forces have been at play.

A not so relatable past

The key issue – which in my opinion we typically miss in these discussions – is that we try to look at it from an absolute perspective which doesn’t take into account environmental differences.

For (most of) us today, marriage is an individual choice based on the fulfilment of personal ideals and desire. We marry for love, because we met someone special with whom we desire to spend our life together until death (or divorce) do us part. It is about our own happiness (well, I guess often that depends on how far into the marriage you ask people this…), and a “right” to have (hence, for example, also the “right” to marry for same-sex couples, an other contentious point which brings out the worst of many people).

While this perspective makes perfect sense to us, it is very far from what used to be the everyday reality back then. Marriage was not a right or a pleasure, but largely a duty towards other people (and often God itself). It was a fulfilment of the whole divinity, and a response to the needs of the society. Nowadays we consider, in a way, individual human beings to be “whole” and divine within their own self and ambitions. This is also what we mean when we discuss gender equality from a modern perspective. Men and women are “equal” in the sense that every person has on their own a fully formed dignity, independence and perfect fulfilment of their needs. A woman (or a man, although typically there is less emphasis on this apect), is on her own capable to be a parent, a worker, a student, and a fully formed member of the society.

You can question whether or not men and women are equal in front of the divinity in various religious tradition. That would be a complex discussion with potentially fair points on both sides, but that would be beyond the present topic. Even if you do consider man and woman to be “equal” in any specific religion tradition, though, that idea is certainly inconsistent with today’s dominant view on equality I described above (implying a man and a woman are “the same”). You may (reasonably) argue for man and woman to be equally valuable, but in ancient tradition this typically happened through complementarity. The idea has usually been that the masculine and the feminine are different and meant to create a divine unity by complementing each other.

There are numerous examples of this from multiple different traditions. In Plato’s “soul mate” myth, human beings originally had four arms, four legs, a single head made of two faces, and sometimes both genitalia. These original being were powerful, wise, nearly divine, to the extent the actual gods felt treathened by them. Zeus solved the issue by splitting them in half, so that each human would then only have one set of genitalia. Throughout their lives, these halved beings would long to find the other half of their soul, and reconstitute the original, nearly divine entity which fully expressed both the masculine and feminine principle.

Within Indian traditions, many focus and the marriage of the god Shiva and the goddes Shakti. The union of a man and a woman in marriage, or even more specifically in a sexual act, has a great spiritual significance. It represents the union of the spirit of Shiva and Shakti which resides in them. Through that union of consciousness and energy the full divine power of creation is unlocked.

These sort of ideals come with several potential critical issues. For example, the idea of a “soul mate” may practically lead to all sort of troubles, such as having people being unwilling to settle down in the perpetual search of an unrealistic “perfect” partner or, even worse, sticking to an abusive parter who they believe to be “the one”. An other possible criticism is that this emphasises a stereotypical perception of fixed gender roles, or that it may denigrate homosexuality. Once more, that would be an interesting topic to discuss, but I’ll leave that to some other time. Let me briefly point out though that it is not necessary to assume that the union of masculinity and femininity must mean the sexual union of a human male and female. For instance David Deida ( a writer who focuses on the sexual and spiritual relationship between men and women) makes in my opinion a brilliant job in detailing the difference between the principles of masculinity and feminity while avoiding this problem. In his writing, he emphasises that both men and women, straight or not, do possess both the masculine and feminine principle (although frequently in different doses, typically but not necessarily a man being more masculine and a woman more feminine), and that the more both parties develop both principles, the better.

I don’t think he is merely trying to “save the appearances” either. Arguably many traditional cultures understood as well that masculinity and femininity were an expression of a polarity between different principles. And, in fact, that the whole reality was best understood as the interactions and complementary of opposites. Light and dark, day and night, matter and energy, order and chaos, death and birth, logical and emotional, active and passive… masculine and feminine. This theme recurs across many cultures, and it is even mirrored in the structure of our own brain, with differentiated roles between the left and right hemispheres.

So, in traditional cultures, the masculine and the feminine were certainly perceived as being different, not equal, and their difference rather than sameness was emphasised. Sure, certain cultures gave more relevance to an aspect rather then the other (typically in reponse to a perceived unbalance). For instance you could argue that taoism focuses more on the “feminine” principle, and taoism was born largely to bring balance to the perceived insistence of confucianism on the “masculine” principle. In general, though, the masculine and the feminine are perceived as complementary forces which can only achieve divinity through the harmonious union of both of them. This is visually expressed in the Tao.

Personally, I see in this theological emphasis on the divinity of the union of masculine and feminine and on their newly found creative power as the attempt to bring a sacred element to human life and its everyday challenges. I see this as one of the foundational motives of religion and spirituality (as I already described when talking about the holy sound of thunder). As the Buddha pointed out, the ultimate and unavoidable reality of life is continuous suffering through a precarious state of impermanence which can only lead to the loss of everything we love, including eventually our own life. Religion have always been an attempt to find something “sacred” through this, something worth living for. But, as such, they can’t address exclusively an innate and eternal psychological need. All of this doesn’t exist in a void, and it is largely rooted in practical considerations about life and the struggles it comes with. Which may be very different depending on the location or moment in history we look at.

How tradition reflects the environment

Once more, I am not here to argue for or against either a traditional perspective of complementarity or modern perspective of equality (meaning “sameness”). My today’s attempt is simply to discuss why and how a certain perspective emerges, and which sort of conditions favour the birth of a certain perspective over others.

Our view of equality as man and woman being “the same” and independent one of an other is not just a matter of “human rights” or of an “enlightened” outlook on life. It is, first and foremost, a material possibility which emerged through peculiar environmental factors. Namingly, the fact that we can be independent and “whole” on our own because we have the financial and technological resources to be so. Today both men and women have easy access to a career, an education, a child, a sexually fulfilling life, a wealthy lifestyle. They can choose which of those they want. They may even choose to simultaneously pursue all of them, and obtain all of it with easy. They don’t need marriage for that. Thanks to birth control, we can choose to have daily sex without ever having to deal with the responsabilities of parenthood unless we want to. We have easy access to children, and due to easy access to childcare or welfare systems we can choose to be parents with only minor consequences on the quality of other aspect of our life.

I’m not making a joke of the difficulties of modern life. I am a father, outside of marriage. My productivity, my finances, my leasure time and many other things are impacted by the fact I have a daughter. Parenthood comes with difficulties, particulary the responsabilities of making the right choices for the sake of an other human being entirely dependent on you. It’s no joke and it is not easy to do be a “good father” (although, as I pointed out in “Why I don’t want to be a good father“, that may not be the best way to phrase it). But no matter what the difficulties of being a parent in general, and even more specifically being a parent without the help of a supporting partner may be… Nor how to achieve a truly fulfilling work/life balance may be challenging for most of us… It is nothing compared to the horror-like reality of the past.

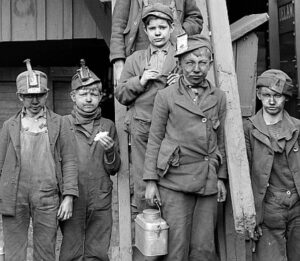

Being a single parent may have easily meant your child dies in your arms because you have nothing to feed them with. And that if you wanted to have some heterosexual sex, you constantly had to take into account you were very likely to become a parent (probably a single one, unless you had a “secure” partner). Having a “career” mostly meant doing a unfulfilling job maybe 12-14 hours a day, just to have a piece of bread at the end of it. If you were lucky. Maybe starting when you were a 6-years old child until the day you died.

For you and me, to get married is a (hopefully) pleasant option. Yes, after marriage our lives could be far better or far worse (say, financially, emotionally, or anything else). But it is just a potential addition, not (necessarily) a goal for life or a survival need. We can enjoy sex outside marriage or without becoming parents against our desire. We can be successful parents outside of marriage. We can have our cake and eat it too. For us, it is about pleasure and individual fulfilment, and the struggle for survival is so far away that most of us don’t ever need to take it into account. For most people throughout history, that was not the case. It was part of everyday life and, to keep the religious atmosphere, the fires of Hell were at the doorstep of every choice we made.

So, marriage was about duty and survival, not inherently love, pleasure or other fancy things. From this perspective, a woman’s duty was to her husband, to her children, and to God. Practically, the duty was mainly childbirth and childrearing. A man’s duty was to his wife, his children, and to God. Practically, the duty was mainly to protect the family and providing their means of survival. Basically it is about putting the family unit and its needs at the center of society (rather then the individual and their need, as happens today).

Marriage was intented to meet several needs (both for the parents and even more for the children), but let’s discuss two basic and crucial ones:

a) the man’s paternity

b) the woman’s financial security and safety

This obviously goes both ways to some extent, but there is a clear disparity in the pressure to have them. The woman desire for maternity is equal to that of a man, but she has a privileged access to it. First of all, she can’t be easily a victim of maternity fraud. A husband can witness the birth of an other man’s child without knowing it: dna testing indicates that something between 1% and up to over 30% of fathers (depending on the specific sample we take) are not, in fact, genetically related to their children. On the contrary, a mother will never have some other woman’s child grow in her womb. Additionally, a woman access to reproduction is way easier than a man is. It turns out we have twice as many female ancestor than males, meaning typically women reproduced twice as often as men. The ratios may have been even more skewed in a few crucial moments of history, such as the advent of agricolture. Thus, the man’s paternity issues are something that requires solving, not because they are more important than a woman’s, but because they are not as easily met.

On the other hand, a woman’s access to the resources needed for survival is crucial, both for her and for society as a whole. First of all, if and when she becomes a mother, she is going to be vulnerable and somehow incapacitated for a long period of time. This may be particularly true for ancient societies without proper medical care or modern tools. But there are other additional factors, regarding her role as potential mother. Le me put it this way. Suppose a society is going to be the victim of an epidemic. Or, to keep the religious narrative, a divine curse! Imagine God talks to them, and tells them that 90% of the members of one gender is going to be killed. They can choose whether 90% of men or 90% of women is going to die. What should they choose? Well, it they decide to spare the men, they basically just committed suicide. The reproductive power of a society of 10 women and 100 men is crippled for generations, and it would be a miracle for them to surive. Instead, the reproductive potential of a society of 100 women and only 10 men is nearly identical to the original one. They are going to face hardship, of course, but the likelihood they will survive is far greater than the previous example.

This is why typically in any society men’s lives are disposable, while women (and children)’s safety is prioritised. If someone has to die and you have the possibility to choose whether it is going to be a man or a woman, a logical society should always choose to sacrifice the men. This hasn’t changed today either. Men are way more likely to be victim of violence, and to work the most dangerous jobs (meaning they are overwhelmingly more likely to die at work). As a consequences, the average lifespan for men is almost always lower than that of women. Yet, whenever you’ll hear about improving conditions and safety for one gender only, it is going to be well received and openly supported only if it is on behalf of women. Identical movements on behalf of men (as in Men Right’s Activism) or even the demand to care equally about people’s safety regardless of gender are typically met with hostility or ridicule (often for good reasons, in my opinion, but I digress).

Once more, this is not because a woman’s life is inherently more valuable than that of man, but because a functional society is almost bound to prioritise women’s safety over that of men.

So: among other complicated things, a society has to face the problem of dealing differentially with a man’s access to paternity and a woman’s access to safety and resources, because for biological reason they have a different relevance and they present different challenges. Now, of course, a society could create a culture which doesn’t take any of this in account. People could decide to pursue predominantly or exclusively goals which have nothing to do with survival or reproduction, and that can be a noble pursue. Even in that case, though, if that hypotethical society doesn’t pass down its culture to the future generations, it’s not going to be very stable nor long lasting.

So, there are multiple ways to deal with these needs. And different societies have found different structures which are capable to do so, which can be, for example either patrilinear or matrilinear. Both monogamy or polygamy are very typical solutions. When polygamy happens, it is typically mild and frequently limited to men taking multiple wives (polygyny). Scenarios where a man have hundreds of wives can and do exist, but they are less common.

Polyandry (when a wife take multiple husbands), on the other hand, can happen but is rare, because the conditions which make it likely are not as common. Polyandry (just as matrilinearity) in general seem to be favoured by less likely circumstances (i.e. a largely skewed sex ratio, or isolation from potential war threats).

The reason why monogamy and polygyny are way more common is because they are “easy” solutions which mostly work in most cases and mostly fulfil both of the crucial needs I described. If there is no sex outside marriage and the marriage is indissoluble, throughout a society most men have an easy access to sex, will be likely to have an offpsring, and they will be sure their offspring will be in fact their own. Women, on the other hand, will be sure that their protection and their access to resources will be ensured regardless the position of vulnerability which they may end to be in throughout motherhood, and will have a warranty against men who would have merely pleasurable sex with her (and, since the lack of contraceptives, probably impregnate her) and then desert her. Of course, this assumes everyone is going to play by the rules (which obviously they are not), but this is beyond the point. When people create rules for the society, they are creating an ideal scenario to enforce. How well that works is a whole different story (and history shows that frequently when people design a sytem to deal with certain problems, they may just create a mess).

So, what about polygyny, then? Well, it is easy to see that it doesn’t really violates any of the needs described above. The man’s paternity is still ensured, while the woman’s protection and access to resources is still ensured as well. Notice again one important thing: when polygyny happens, it is typically mild and reserved to only a few (powerful) men. Assuming the number of men and women within a society is similar, this is obvious from a simple mathematical perspective: you can’t have most men having multiple wives, while most women have only one husband. As such, polygyny is generally an opportunity rather than a rule. This can be seen in the Quran itself, which states a man could take up to four wives… but he probably shouldn’t, unless he is sure he can fulfill his duties and treat justly each of his wives (Quran 4:3). The key word is, again, duty. It is not a “right” for the man to fulfil his lust with multiple people, but his promise to God to take care of his wives. And the wife herself, in fact, may be better off being the fourth wife a powerful man as compared to the only one of a husband who is uncapable to fulfil his marital duties. Actually in Islam it seems to be implied, in my opinion, that polygyny was largely for this reason (i.e. promote the creation of a family unit for widows and their children). For most people, though, monogamy is still prescribed. With good reason, apparently, since human are naturally a sexually jealous species. Looking up at people who nowadays choose polyamory and are socially free to do so, it seems that the presence of multiple partners tends to be a stressor to the relationship (regardless of which is the “overrepresented” gender).

What about polyandry then? Well, it is a possible system, and there are several societies which arranged themselves that way. It is not as easy though. A polyandrous society has to answer several questions. For example, why should a man be willing to sacrifice his possessions, practical efforts (in some societies and for a poor man, this may mean an intense, unfulfilling and hard physical work on a daily basis) and possibly his life for the sake of an offspring which he has no idea whether or not it is his own. Some polyandrous societies hold religious beliefs that provides an answer to this dilemma. They may believe that the father either does not contribute biologically to the offspring, that a child has multiple fathers since pregnancy occurs as the cumulative result of multiple sexual intercourses (as in some South American societies), or that sex isn’t a cause of pregnancy in the first place (as in the Trobriand islands).

Alternatively, the society needs to find ways to ensure protection and resources to a woman outside of the traditional form of what we call “marriage”. An option could be a matrilinear society. When women are the main or only property owners, the role of the husband as a protector or provider becomes superfluous. In fact, the “husband” may not even live with the wife altogether. In some societies where men don’t own property (for example, the Mosuo), they may live in the household of their mothers and sisters, and mainly focus into raising their nephews. They may be invited over the “wife”‘s home to spend the night or visit their own children, but their contribution to their offspring and the wive’s life is negligible.

Notice that even in these societies polyandrous behaviour may be not common. Frequentlly, when women have power, they won’t pursue polyandry. This is exactly what you see in today’s society as well. Lifelong marriage is increasingly rare and through sexual liberation “polyandrous” behaviour outside marriage (and polyamory in general) is on the rise. Most people though, women in particular, tend to opt for serial monogamy: having one partner at a time and not “cheating” on them while that “pact” exists, even if there is no promise to maintain that relationship indefinitely (and it is understood it is probably not going to be long lasting, given the constantly growing divorce rates).

So, what about us? Where, in general, our own modern society falls in that spectrum? As I said, we tend to think of marriage as an individual’s right and as a possible journey towards the fulfilment of their own needs. We tend to marry the person which we fall in love with, and we tend to divorce the person we fall out of love from. What we tend to prioritise in marriage is individual needs (hopefully, those of all parties involved), from sexual to emotional satisfaction.

This is largely a great thing, and as such we tend to criticise the less “enlightened”, oppressive, sometimes inhumane ways of living in the past. Frequently we fail to realise, though, that this a privilege we have, rather than a more developed moral stance. The way we live today is largely because of the privilege we have. Through the wars fought (and won) by our ancestors, we have a disproportionate access to resources, safety, and potential lifestyle choices compared to any other human being who ever lived. We have the opportunity to be uniquely concerned about our own wellbeing and our own happiness. For the sake of having chosen the best location and moment of time in human history to be born in, everyone of us has the option to think about how to arrange their life accordingly to the fulfilment of their individual desires. A single mother (or father, of course, although that is a less common scenario), has more wealth, safety and options than a king or ruler of the past. We can choose a polyamorous, monogamous, polyandorus or polygamous lifestyle, based exclusively on the content of our hearts. We can choose celibacy or constant sexual promiscuity, without significant consequences. We can discuss sex, relationship and marriage from the perspective of individual rights, desires and fulfilment. That happens largely because we are the rich and powerful people, and rich and powerful people do as they please.

And there is nothing wrong being rich and privileged in itself (quite the opposite). It brings in some questions and some challenges, though. Such as, now that we can basically do whatever we like and pursue whatever we want in life, what should we be doing, and which goals are worth pursuing? And finding an answer to that (from the perspective of intimate relationship and anything else in life) is not an easy task.

And in my experience, one of the biggest issues we face is that we tend to have a lot of troubles understanding past populations or different traditions. We often ask ourselves why people believed certain things, or behaved in a certain way (including major and horrific events in history, such as the Holocaust). And we often scratch our head in confusion, unable to explain it to ourselves. In fact, it was largely to find an answer to these sort of question that I became interested in the study of psychology and human behavior (and, later on, religion and spirituality). And this is the reason why these sort of condiserations pop out frequently in my work, books ar articles. For instance, it’s precisely for this reason that most of the final chapters of The (Subtle) Evil Demon deal with the why and how people in the past participated (and keep participating today) in monstruous behavior.

Conclusion

There is a quote which reflects all we discussed and I can’t express how much I appreciate it: “the greatest discovery of psychology is that human behaviour is not about who we are, but rather where we are“. Thus, when we try to understand different cultures, the first thing we need to take into consideration is what sort of environment they are/were in, and which sort of struggles or needs that environment presents.

First and foremost, this is useful as a tool to better understand both human nature and the deep forces beyond different traditions. Second, it provides insight in the uniquess of the historical moment we are living in, and the new potential and challenges it comes with. Third, why not, it can provide us with important informations to use in the ongoing discussion of our times about which ways to live our lives are valuable today.

Last, but definitely not least, my hope is that figuring out what is behind religious traditions and human behaviour in general will help us to create a climate with more tolerance, openness and mutual understanding in which to carry out this discourse. Which is something I think we desperately need.

+ There are no comments

Add yours